Abstract

Molecular docking is a computational technique used in drug discovery to predict how small molecules (ligands) fit into the three-dimensional binding site of a target protein. By modeling these interactions, researchers can rapidly prioritize compounds that are most likely to bind strongly to the target, accelerating the design of new therapeutics. Physics-based docking relies on empirical force fields and can take minutes per compound. By contrast, AI-driven docking can predict a final ligand pose in a few seconds and inherently captures complex interaction patterns. AI delivers a higher fraction of correct poses. Even greater gains emerge when AI’s predicted poses are followed by a brief physics-based minimization step (exemplified with ArtiDock+UFF and ArtiDock+Vina in the article), raising overall accuracy further without adding substantial computation time. In challenging cases, such as binding sites with metal ions, organic cofactors, or structured water molecules, this AI+physics combination demonstrates markedly better accuracy and interaction fidelity.

Introduction

Molecular docking is a computational technique used in drug discovery to predict how small molecules (ligands) fit into the three-dimensional binding site of a target protein, a biomolecule whose malfunction or dysregulation causes a disease [1]. By modeling these interactions, researchers can rapidly prioritize compounds that are most likely to bind strongly to the target, accelerating the design of new therapeutics.

Physics-based docking methods rely on established physical principles: modeling electrostatics, van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonds, and desolvation via empirical force fields. These algorithms systematically explore ligand placements and compute an energy score for each. While they have powered virtual screening for decades, they can take minutes per compound and often struggle with challenging cases like metal-coordinating sites or structured water networks [2]. By contrast, AI-driven docking replaces hand-tuned energy functions with neural networks trained on thousands of known protein-ligand complexes. A trained AI model can predict a final ligand pose in a few seconds, enabling the rapid screening of millions of compounds, and inherently captures complex interaction patterns that are hard to encode in traditional force fields [3].

Overall Outperformance

To assess the performance of protein-ligand docking methods, researchers rely on benchmarks, curated collections of experimentally solved complexes that span diverse protein families and ligand chemistries. By running each algorithm on the same set and comparing predicted ligand poses against the true binding modes, we obtain directly comparable accuracy. In our study, we utilized the PoseX benchmark dataset, which reflects the variety of challenges encountered in real-world drug-discovery

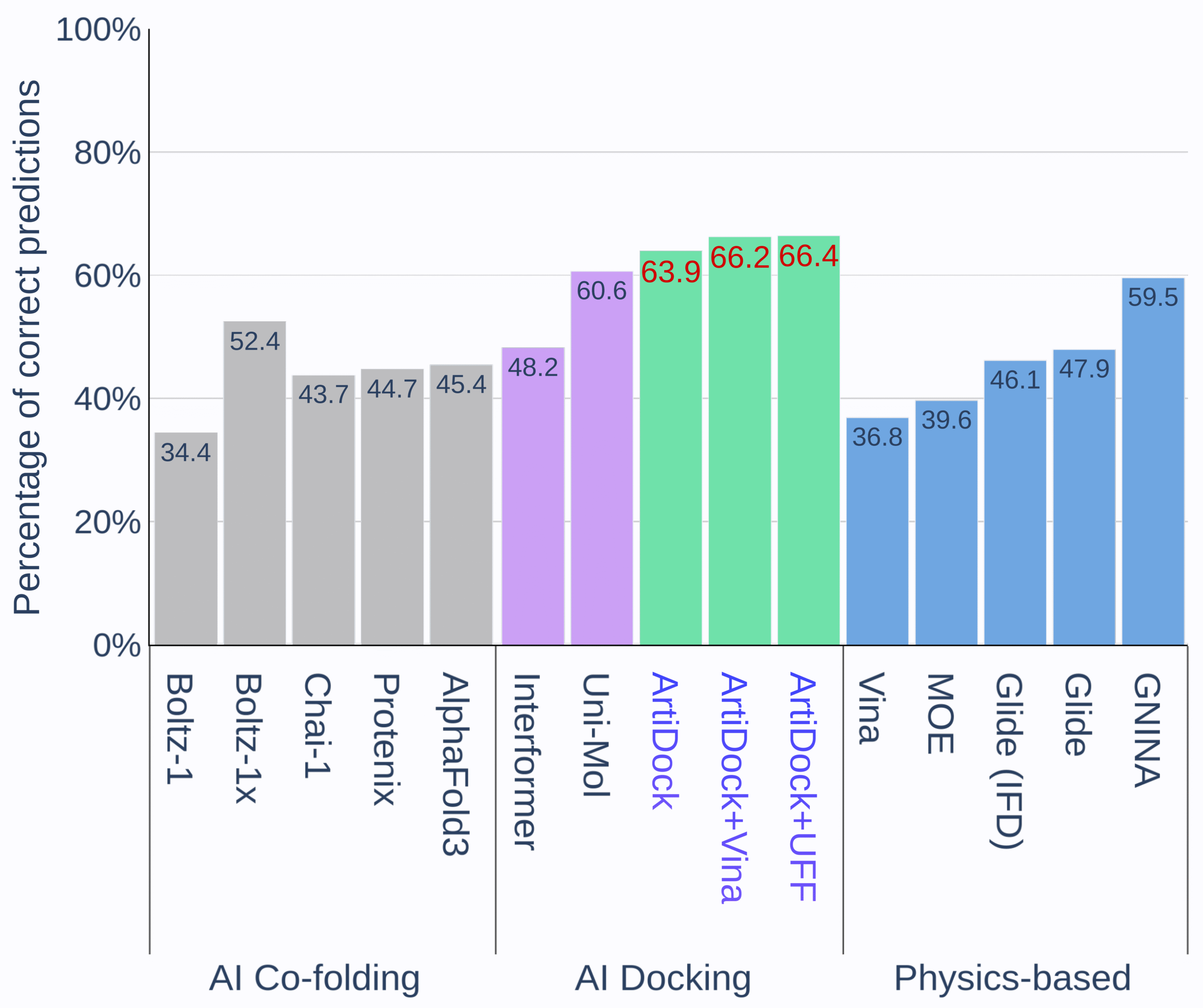

projects. Results are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Percentage of correct predictions by protein-ligand docking methods in PoseX benchmark. [Credit: Receptor.AI]

Pure AI-driven docking engines such as ArtiDock and Uni-Mol deliver a higher fraction of correct poses than classic force-field methods like AutoDock Vina or Glide. By learning directly from thousands of solved structures, these AI models capture intricate interaction patterns that rigid scoring functions often miss, translating into consistently superior pose-prediction rates. Even greater gains emerge when ArtiDock’s AI-predicted poses are followed by a brief physics-based refinement. In this hybrid workflow, ArtiDock first proposes the most likely binding geometry within seconds, and then either Vina or Universal Force Field (UFF) minimization smooths out any remaining steric clashes or strain. Because the neural network has already pinpointed the correct region and orientation, this additional step raises overall accuracy further without adding substantial computation time (ArtiDock+Vina and ArtiDock+UFF on Figure 1).

Co-folding models like AlphaFold 3, Boltz-1x, and Protenix aim to predict the protein pocket and dock the ligand in one go. While this unified approach can be useful, especially for targets without high-resolution structures, their current accuracy remains below both specialized AI docking and physics-based methods [4].

Performance in Difficult Areas

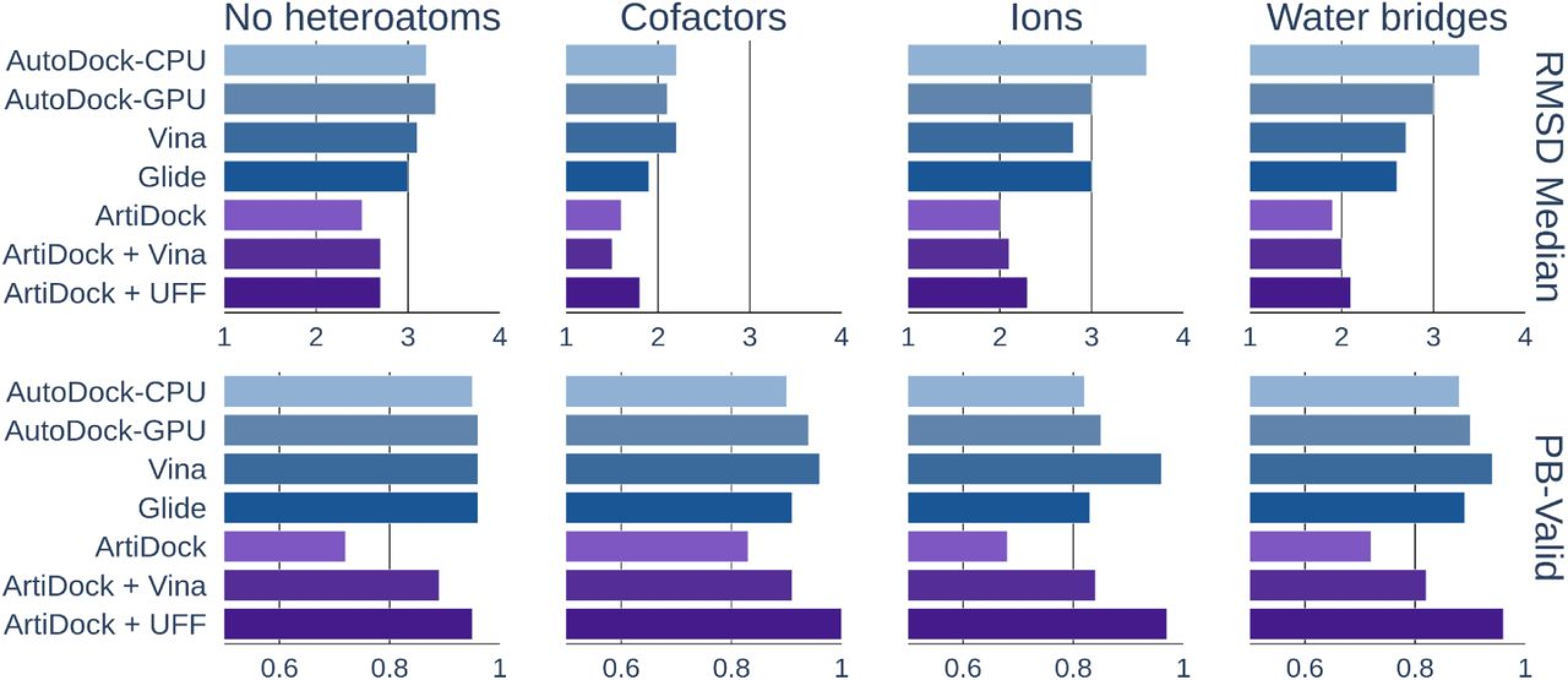

Docking becomes especially challenging when the binding site contains non-protein entities such as metal ions, organic cofactors, or structured water molecules. In these scenarios, traditional force-field methods struggle because generic parameter sets often fail to capture the precise coordination geometry of metal centers, the directional hydrogen-bonding networks of water bridges, and the unique electronic environments around cofactors. As a result, physics-based tools like AutoDock Vina or Glide can misplace ligands or generate poses that clash sterically or lack key interactions, limiting their reliability in realistic drug discovery pockets [2, 5, 6].

Figure 2. ArtiDock performance in pockets containing no heteroatoms, cofactors, ions, or bound water: median RMSD (root-mean-square deviation, in Å) and PB-Valid (fraction of poses passing PoseBusters quality checks). [Credit: Receptor.AI]

In contrast, ArtiDock demonstrates markedly better accuracy and interaction fidelity across all tested difficult-site categories (Figure 2). By learning directly from diverse structural examples, including those with metals, water networks, and cofactors, its neural network internalizes the complex patterns of coordination and solvation that traditional scoring functions miss. Consequently, ArtiDock yields lower median RMSD values and reproduces more of the true protein-ligand contact network, maintaining correct geometry even before any additional refinement.

Adding a short physics-based minimization step using either Vina rescoring or Universal Force Field (UFF) energy minimization introduces a small uptick in RMSD, since the energy optimizer may subtly shift the pose. However, this trade-off is counterbalanced by a significant increase in chemical validity, restoring or strengthening key interactions.

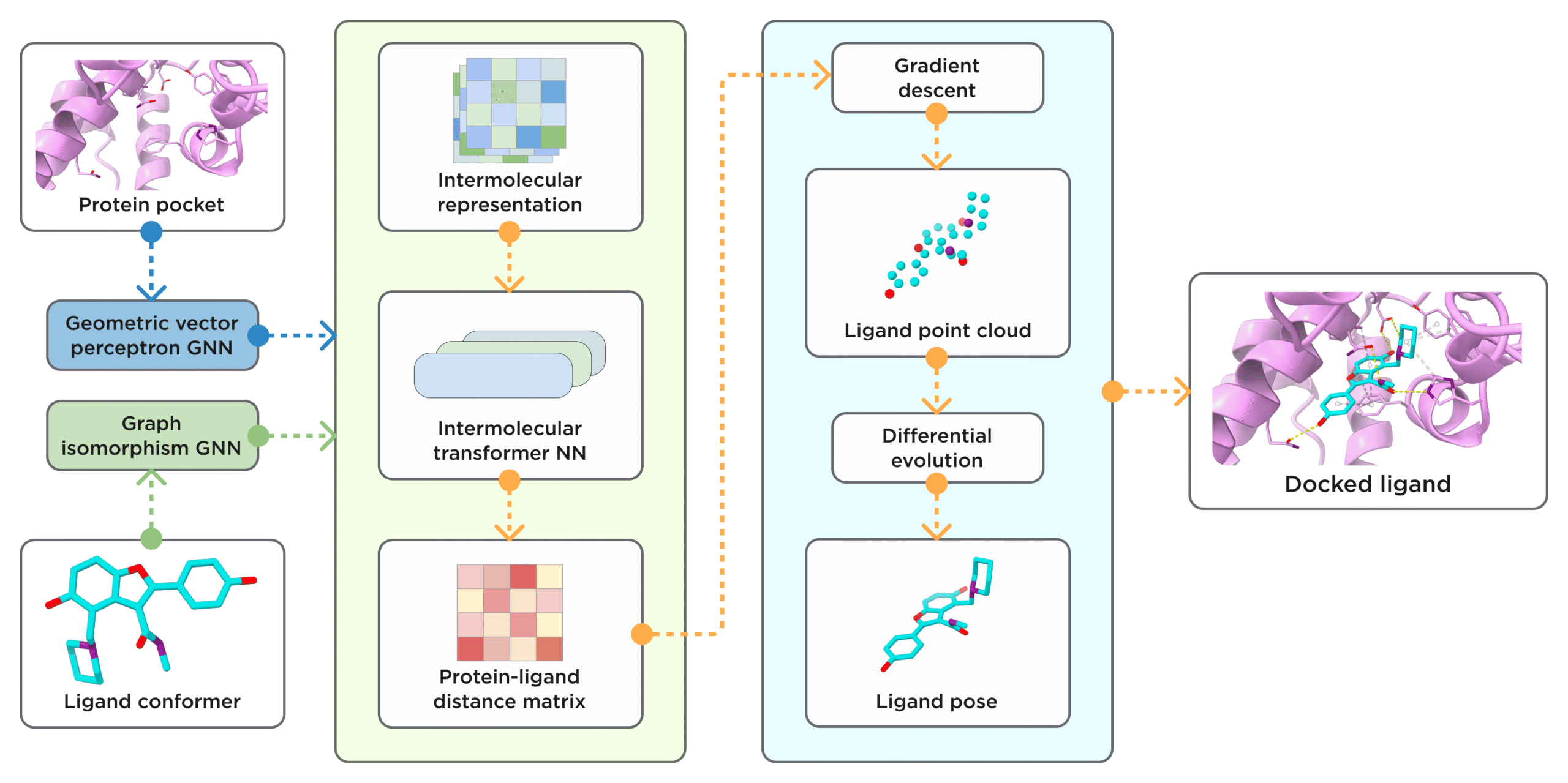

How It Works: ArtiDock Architecture

Receptor.AI’s ArtiDock starts by converting the protein binding site and the small molecule ligand into simple graph representations (workflow in Figure 3). The ligand is modeled as a network of atoms connected by bonds, while the protein pocket is captured as a set of nearby heavy atoms annotated with basic chemical and spatial features: enough to describe the pocket’s shape and environment without overwhelming detail [7].

Figure 3. General scheme of ArtiDock model architecture and inference pipeline. [Credit: Receptor.AI]

A lightweight neural network then learns how these two graphs fit together. By examining many examples of known protein–ligand complexes, ArtiDock infers the ideal distances between each ligand atom and the surrounding pocket atoms. This learned distance matrix effectively encodes the best way for the ligand to nestle into the target site [7].

Finally, a fast procedure converts the predicted distances into a three-dimensional pose. It aligns a pre-generated ligand conformation to match the learned distance pattern, producing a realistic placement of the compound in the pocket. This direct prediction approach bypasses the lengthy trial-and-error cycles of traditional docking, delivering accurate poses in a fraction of the time [7].

Conclusion

AI-driven docking tools like ArtiDock have shown that models trained on large, diverse structural datasets can overcome the speed and accuracy limits of traditional physics-based methods. By delivering precise poses in seconds, even in the most challenging binding sites, these AI approaches promise to accelerate drug discovery.

Further details regarding ArtiDock can be found here.

References

1. Kitchen DB, Decornez H, Furr JR, Bajorath J. Docking and scoring in virtual screening for drug discovery: methods and applications. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2004;3(11):935–949. doi:10.1038/nrd1549

2. Eberhardt J, Santos-Martins D, Tillack AF, Forli S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: New docking methods,expanded force field, and Python bindings. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 2021;61(8):3891–3898. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00203

3. Alcaide E, Gao Z, Ke G, et al. Uni-Mol Docking V2: Towards realistic and accurate binding pose prediction. arXiv. 2024;2405.11769. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2405.11769

4. Abramson J, Adler J, Dunger J et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630, 493–500 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07487-w

5. Riccardi L, Genna V, De Vivo M. Metal–ligand interactions in drug design. Nat Rev Chem. 2018;2(7):100–112. doi: 10.1038/s41570-018-0018-6

6. Hu X, Maffucci I, Contini A. Advances in the Treatment of Explicit Water Molecules in Docking and Binding Free Energy Calculations. Curr Med Chem. 2019;26(42):7598-7622. doi:

10.2174/0929867325666180514110824

7. Voitsitskyi, T., Koleiev, I., Stratiichuk, R., Kot, O., Kyrylenko, R., Savchenko, I., Husak, V., Yesylevskyy, S., Starosyla, S., & Nafiiev, A. (2025). ArtiDock: accurate machine learning approach to protein–ligand docking optimized for high‑throughput virtual screening. bioRxiv, 2024.03.14.585019 (v2). https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.03.14.585019